The 62nd IMCL Conference will study the many important lessons of this stunning renaissance - including the genetic intelligence of revival architectures

ABOVE: The transition in Potsdam from a grim "modern" urbanism to the more humanist landscape of prewar Germany, as shown in a remarkable video by The Aesthetic City (click to view). New research shows that the older city in fact demonstrates a more "modern" scientific understanding of the best human environments and their characteristic geometries.

POTSDAM, GERMANY - From October 15th through 19th this year, the 40th Anniversary International Making Cities Livable (IMCL) conference will be held in this beautiful city, with an exceptionally rich history of urban and architectural patterns. The locale also offers a case study in the new scientific understanding of the power of evolutionary refinement, and the "collective intelligence" embodied in the best human environments.

The IMCL conferences are always focused on finding the best solutions to meet our urban challenges, from whatever source and whatever period. We do that by gathering to share knowledge at instructive and inspiring locales. Some of the best solutions will often be fresh and innovative -- but many of the best ones will have evolved through careful refinement over decades and centuries, arising from the complex workings of human collective intelligence. These solutions often take the form of rich and useful patterns, expressed in the most successful, well-loved and enduring places today.

But there is a peculiar idea circulating nowadays, one that is still dominant in too many circles -- that such patterns are no longer relevant, that they are laden with too much of the political baggage of the past, or they are simply not "authentic" to a "modern" era.

Let us call this idea what it is. It is idiocy. And it is disproven by a growing body of evidence.

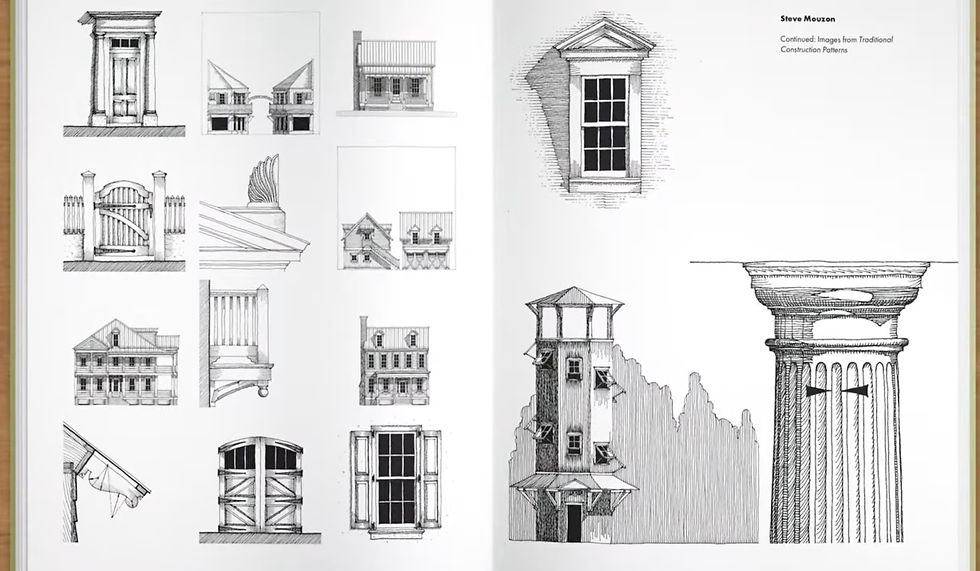

New findings in the sciences demonstrate clearly that human environments, like other structures in the Universe, typically evolve, differentiate and refine over time. Through their structural evolution, and the actions of the distributed agents who serve as human contributors, these places grow more rich and more beautiful, and they expand their capacity to improve the well-being and health of people and place. They are not less sophisticated than most novel solutions: indeed, they are often more so.

Sometimes too, the beautiful and successful patterns of the past suffer catastrophes, and their memory brings discomfort. Sometimes they are associated with painful periods of history, and there is a temptation to forget about them, and to "move on." This has been the case in Potsdam, Germany, the beautiful royal city of Prussia built by and for Prussian kings and German Emperors prior to 1918. Following the city's near-total destruction in World War II, however, while there was a general desire to preserve a few museum pieces from its history, the rest of the city was to be replaced by more "appropriate" or "authentic" contemporary buildings. The results were... not satisfactory, by the judgments of most people.

This "modern" approach failed to recognize the embodied intelligence of the previous patterns -- not merely as historic relics, but as living patterns of what Kevin Lynch called "good city form." Instead of understanding how such structures could improve human life and health, planners and architects in Potsdam, as in other places, made a series of crude and catastrophic mistakes: too many cars and roads, too many cold blank buildings, too many fragmented, isolating, deadening places.

This was not collective intelligence, but collective stupidity.

ABOVE: The Alter Markt area today.

New research is demonstrating that, far from incorporating "backward" or "inauthentic" patterns -- as some architectural ideologues still claim -- Potsdam and other historic cities embody highly intelligent and still-useful patterns of human settlement, capable of enduring, and indeed of promoting human flourishing. While they may express particular stylistic or culturally unique symbolic characteristics, they also typically incorporate deeper universal patterns of life-enhancing environmental structure -- patterns that are not only still relevant today, but are essential in meeting our daunting urban and planetary challenges.

The fallacy that such places are "backward" and no longer "appropriate to our time" is easily disproven by the evident fact that such patterns, when revived, have produced some of the most successful and best-loved places in human history, even up to the present day. (Their ecological performance is often far superior too, which is not a coincidence.) The success rate of "modern" environments, by comparison is -- let us not mince words -- dismal.

Nor are these patterns only useful in reconstructing historic environments. They are also demonstrably beneficial in creating wholly new buildings and neighborhoods, applying the enriching capacities of traditional patterns and characteristics. (And of course, new expressions can always be added to the old -- as was always the case in the "fugue" of history.)

There is demonstrable and growing evidence that these patterns are superior, that they have salutary effects, and that to deny their benefits to our clients and the public increasingly appears to be -- to put it bluntly -- an unconscionable form of professional malpractice.

While the IMCL conferences share practical and research knowledge about making cities livable from around the world -- and embracing local architectures from local places -- one of the most valuable experiences of the IMCL conferences is the opportunity to learn from the locales where the conferences are located. In that sense, Potsdam is an especially fitting venue: it offers a "teachable moment" about the tragic events and miscalculations of its history, as well as the intelligent beauty of its patterns, and the opportunities for their revival.

As a case study, we will learn about Potsdam's sad fate during World War II, when the city became the target of devastating Allied bombing. Its beautiful Alter Markt square, with stunning architectural treasures (including St. Nicholas Church designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel), was almost totally destroyed.

ABOVE: The Alter Markt after bombing.

Another form of devastation happened after the war, when the East German government replaced many of Potsdam's remaining beautiful historic buildings with "modern" buildings that could most charitably be called "expedient." While the older buildings reflected centuries of architectural evolution and refinement, the new structures followed the dictates of early 20th century architecture to "start from zero" (Gropius), to let "mechanization take command" (Giedion), and to redefine architecture as "machines for living in" (Le Corbusier). At best, such buildings served as gigantic sculptures, more attentive to the artistic prerogatives of the architects than to the needs and desires of the users and citizens. While such buildings are still often popular with architects, research surveys show that most non-architects find them ugly, uninviting, and even dispiriting. Evidence for the success of this regime, from a broader human point of view, can best be described as "unsatisfactory".

Indeed, recent research has begun to show that such buildings and settlement patterns are not merely unpleasant to their occupants -- they have a negative impact on the health and well-being of all who have to live in and around them. (We will explore some of this research evidence at the conference.) They also have an indirect impact on the health of natural ecologies, relying as they do on mechanized and functionally segregated systems including automobiles, highways, concrete infrastructure, parking lots, and many other ecologically disruptive structures. These places are much less reliant on pedestrian movement at more compact human scales, and they sacrifice the vital benefits of face-to-face interaction within inviting public spaces. (Slapping them into fragmented park-like settings seems to have only partially mitigating effects, and might constitute a form of "greenwashing".)

But in this light, the more recent history of Potsdam is inspiring. The city has entered a new chapter as a much more livable city, featuring a stunning revival of many of its historic buildings as well as new buildings built on traditional patterns. During the planning of these projects, there has been heated debate about whether this revival was "authentic" -- often pitting isolated architectural ideologues against larger citizen groups and professionals from outside the profession of architecture. The tide seems to be turning against the ideologues, who appear increasingly isolated. A proper assessment of the new research evidence -- not ideological cant, rigid habits or orthodox dogma from the previous century -- is long overdue. (Talk about those mired in the past!)

We will hear from some of the people who were responsible for Potsdam's renaissance, and learn from their challenges and successes. They include Thomas Albrecht, one of the architects of the transformation. We will have an opportunity to debate the issues and examine the actual evidence. (Certainly, let us invite those who defend the modernist status quo to present their case.) And of course we will learn about many other case studies and research findings from around the world, about how to meet our urban and planetary challenges in the ways we shape buildings (and thereafter they shape us) -- and in many other aspects of urban structure and building systems.

We will also hear from our hosts, including Bart Urban of The Aesthetic City (producers of remarkable videos like the one above). They are documenting the changing thinking about what is "modern" and what is universal and humane in our cities, towns and suburbs -- and how to make them healthier, more beautiful, more durable, more just -- and yes, more livable.

While there, we can also enjoy the stunning Sanssouci Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site with many architectural and landscape treasures. A few of these treasures are shown below.

We hope you will join us for an exceptional gathering! https://www.imcl.online/potsdam-2025